sšsšsš

What We've Learned About Reading Comprehension and Effective Instruction

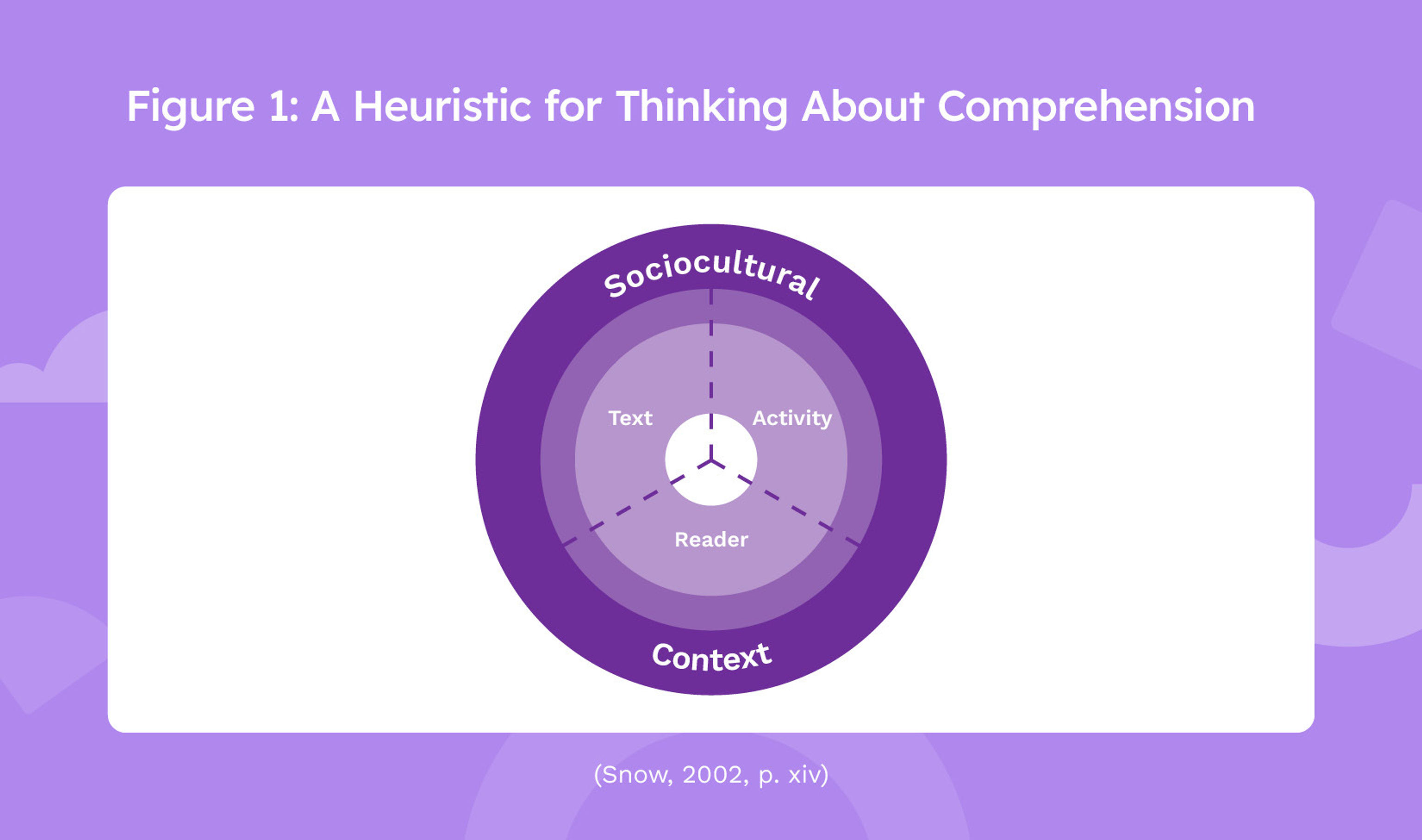

Comprehension is complex and doesn't lend itself easily to definition. But I believe that a Rand Corporation report published back in 2002 remains the best model for understanding how comprehension works and how we can help our students become more skilled at understanding what they read. The Rand Reading Study Group (RRSG), under the leadership of Dr. Catherine Snow, recognized that a definition and description of reading comprehension based on the science was foundational to their work. They defined reading comprehension as "the process of simultaneously extracting and constructing meaning through interaction and involvement with written language."

The terms "extracting and constructing" conveyed both the important role of word recognition (extracting) and the ability to build meaning from print by integrating what is explicitly stated and what is implied in the text (constructing).

The group also acknowledged the multidimensional nature of comprehension by including a description of the three interactive elements that directly contribute to the construction of text. These three dimensions include:

- the reader who is comprehending the text

- the text that is to be comprehended

- the activity which is part of the comprehension [1]

By calling attention to these three elements, the RRSG provided practitioners with a different way of thinking about comprehension and instructional practices.

Understanding the RRSG Model for Thinking About Comprehension

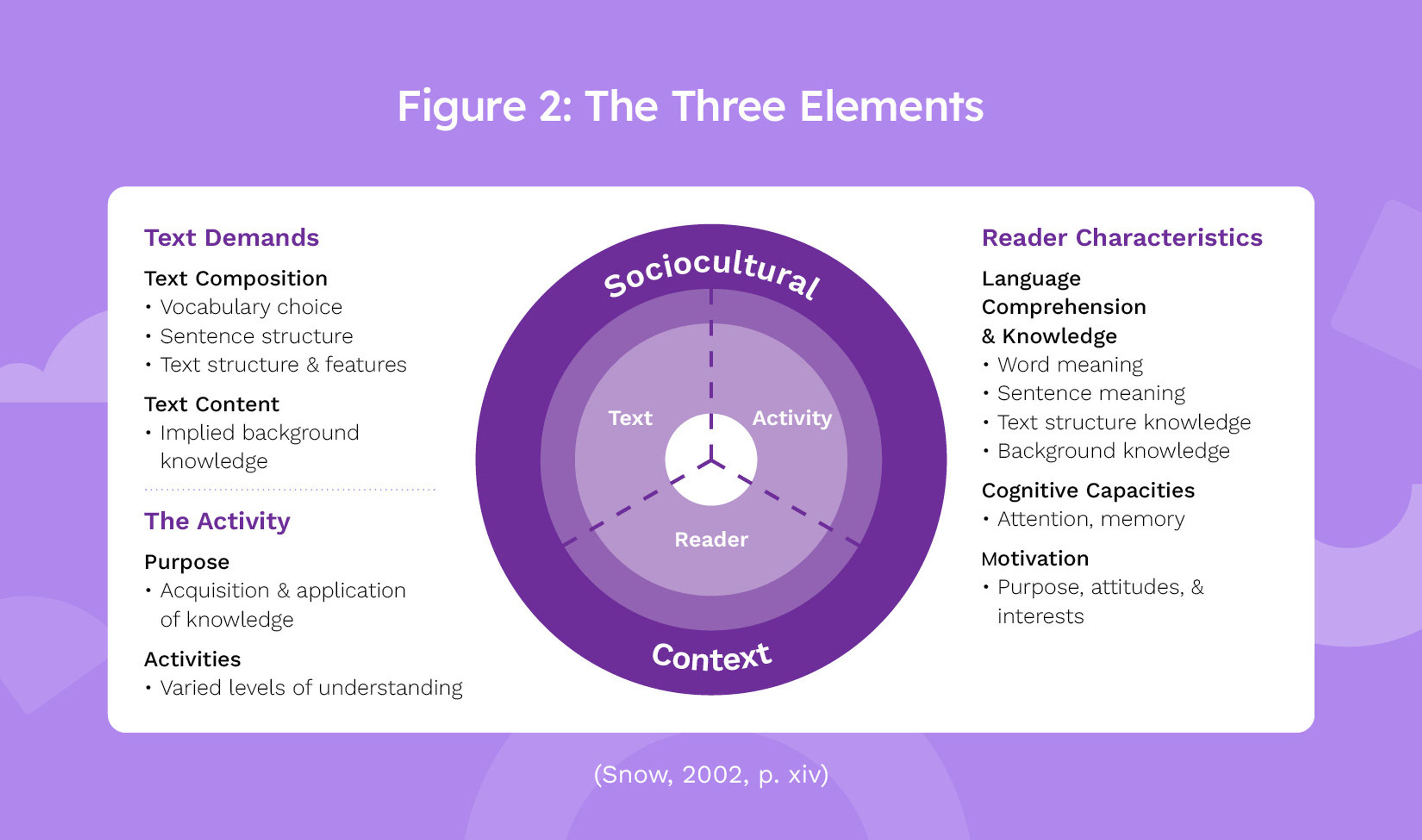

This figure of the Rand heuristic (model) for thinking about comprehension has become synonymous with the Rand Reading Study Group Report.

It provides a window into understanding the dynamic and interactive nature of reading comprehension across time. This visual representation clearly conveys that making meaning is shaped by the interactions of what the reader brings to the text, the demands of the text itself, and the nature of the task, all of which occur within and are influenced by varied environments.

The RRSG described successful comprehension "as what occurs when the demands of the text, the challenges of the task, and the skills and proclivities of the reader are all well aligned." [1] By detailing and providing a visual of this model, the group offers educators insight into designing effective instructional practices for all students.

The Three Elements

To better understand the implications of the Rand heuristic, let's consider the possible factors or characteristics of these three elements that influence comprehension. Critical factors and characteristics are identified in the following figure along with examples. They are then discussed in the paragraph below.

1. Text Demands

Our students encounter varied texts across the grades that can be easy or difficult depending on language use, text features, and content. The author's choice of words and syntactic structures, the background knowledge needed to understand the content, and the cohesiveness of the author's ideas all contribute to the demands the text places on the reader. In other words, the vocabulary and sentence structures, the ways in which ideas are integrated throughout the text, and the prerequisite background knowledge and text structures all support or interfere with comprehending a specific text. For example, texts read in English Language Arts (ELA), science, and social studies classes are typically written in more formal or academic language than the decodable and leveled text used in early grades. This means that vocabulary is more advanced, precise, or domain specific; that sentences are often longer with descriptive phrases; and that paragraphs may contain more than one idea.

To understand the differences, consider the language and knowledge demands of the following sentences from a narrative text and an informational text:

Tomorrow was her birthday and she knew she would be serenaded at sunrise. Papa and the men who lived on the ranch would congregate below her window, their rich, sweet voices singing Las Mananitas, the birthday song.

An excerpt from Esperanza Rising, by Pam Muñoz Ryan, 2000

The first dinosaurs evolved roughly 235 million years ago in the Middle Triassic Period. Their ancestors were small slender archosaur reptiles that stood and walked with their legs underneath their bodies. This upright stance was perfected by the dinosaurs and was one of the factors that allowed many of them to grow so big.

An excerpt from Dinosaur! by John Woodward, 2014

The vocabulary words and sentences in these selections may present challenges, but these texts also demand a knowledge of the specific text structures and content. Some structures (for example, informational text) may be even more challenging because of domain-specific vocabulary, unfamiliar content, and the use of varied paragraph types within one selection.

By identifying this element — the demands a text can put on a reader — the RRSG provides insight into the challenges presented by the text that can and should influence our thinking about text selection as well as how to plan for instruction that scaffolds and supports understanding based on what we know about our students.

2. Reader Characteristics

As the shift occurs from learning to read to reading as a vehicle for learning, the readers' language comprehension abilities and knowledge play an increasingly important role.

A broad as well as precise knowledge of vocabulary is initially necessary to unlock meaning at the word level. However, their understanding of sentence structure is the key to identifying how ideas are constructed and, eventually, integrated to convey meaning. Their knowledge of text structure also helps students to identify the author's purpose and to understand how the content is organized. Meanwhile, the students need relevant background knowledge to infer what is not explicitly stated in the text. In this way, the reader constructs meaning at both literal and inferential levels and ultimately builds an overall understanding of the text itself.

Now, please reconsider the text examples provided above and reflect on what language comprehension skills and knowledge the individual reader would potentially need to effectively work with the text.

An understanding of these factors, along with an awareness of what the Rand Report calls non-linguistic factors (such as cognitive capacities and motivation), is foundational to planning for the individual student. Informed instruction addresses the development of skills and knowledge that align the demands of the text with the reader's abilities.

3. The Activity

We know that comprehension is shaped not only by the interaction between the reader and the text but also by the assigned activities that reflect the purpose of reading. The RRSG reports that readers engage in reading for varied purposes, including entertainment, knowledge, and application. In the school setting, the reason for reading is often to acquire or apply knowledge. Our students may be asked to find facts, draw conclusions, identify themes, write a summary, or apply acquired knowledge in new situations. These varied comprehension tasks require different skills and knowledge. As educators, we need a clear understanding of expected outcomes so that our instruction supports our goals for the lesson and enables students to set their own goals while using strategies and skills appropriately to complete activities successfully.

The All-Encompassing Environment: The Socio-Cultural

The Rand Report acknowledges that all learning takes place within a larger context or environment. While we tend to think of the classroom as the primary environment for learning, our students bring varied experiences that are shaped not only by school but also by their social and cultural surroundings. Differences in these surroundings are often related to income, race, ethnicity, native language, or neighborhood. An awareness of these differences and possible related challenges is critical to providing effective instruction that is based in the science and responsive to the needs of diverse learners.

Reflect & Connect: Now, please reflect on insights gained about comprehension and potential connections or applications to instructional practice.

References

Kirby, S. N. (2003). Developing an R&D Program to Improve Reading Comprehension. Research Brief. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation. Retrieved from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB8024.html

Ryan, P. M. author. (2000). Esperanza Rising. New York, NY: Scholastic Press,

[1] Snow, C.E. (2002). Reading for Understanding: Toward an R&D Program in Reading Comprehension. RAND Corporation, MR-1465-OERI, 2002. As of June 30, 2023: https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1465.html

Snow, C. E. (2010). Reading Comprehension: Reading for Learning. International Encyclopedia of Education, 5, pp. 413-418.

Snow, C. E., & Sweet, A. P. (2003). Reading for Comprehension. In A. P. Sweet, & C. E. Snow (Eds.), Rethinking Reading Comprehension. New York: The Guilford Press.

Woodward, J (2014). Dinosaur! Dinosaurs and Other Amazing Prehistoric Creatures as You've Never Seen Them Before. New York: DK Publishing.

Related Content